New Jersey warehouse filled with copper shows Trump tariff risk

According to me-metals cited from mining.com, The New Jersey wholesaler, which sells to mom-and-pop tradesmen as well as larger-scale builders, is taking a risk that it’ll be stuck with excess inventory if the economy takes a turn and buyers disappear. But Richman didn’t feel like he has much choice given the outlook for costs.

He’s already paying more for copper data-x-items because suppliers to his family-run business boosted prices as much as 12% in the past couple months in anticipation of tariffs. Richman — like others in his shoes — is passing on those higher costs to all but his most loyal customers.

“The consumer is the one who’s losing,” he said in an interview.

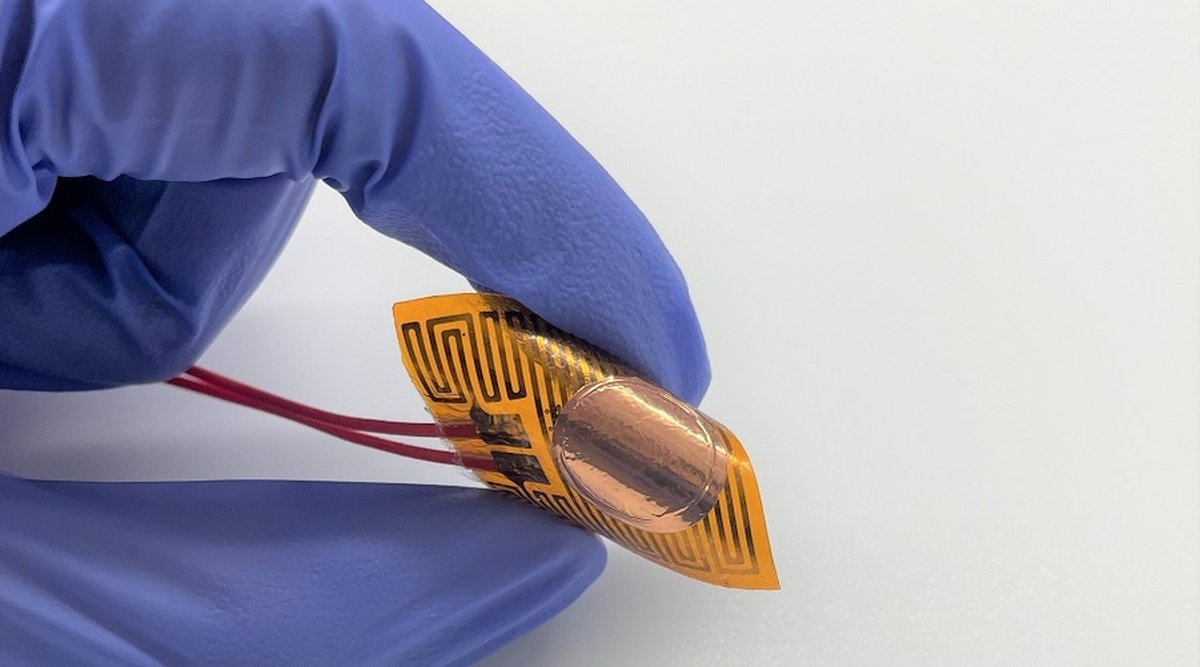

Richman’s situation is similar to what many businesses across the US are going through as President Donald Trump mulls imposing tariffs on copper imports, possibly within weeks. The levies threaten to inflict pain across a broad section of the US economy because of the myriad industries and applications that rely on the metal — everything from automobiles and data centers to home construction and consumer electronics.

Its widespread usage is the reason why the metal is dubbed “Doctor Copper” — a barometer for the health of the economy.

“At the end of the day, tariffs will make US copper more costly for consumers,” said Ewa Manthey, commodity strategist at ING Bank NV. “Higher copper prices might also feed into higher inflation.”

It isn’t certain they’ll be imposed, but Trump first talked about copper tariffs in late January. On Feb. 25, he ordered officials to consider trade measures on the metal, and days later, in a speech to Congress, the president suggested copper imports could be subject to a 25% tariff.

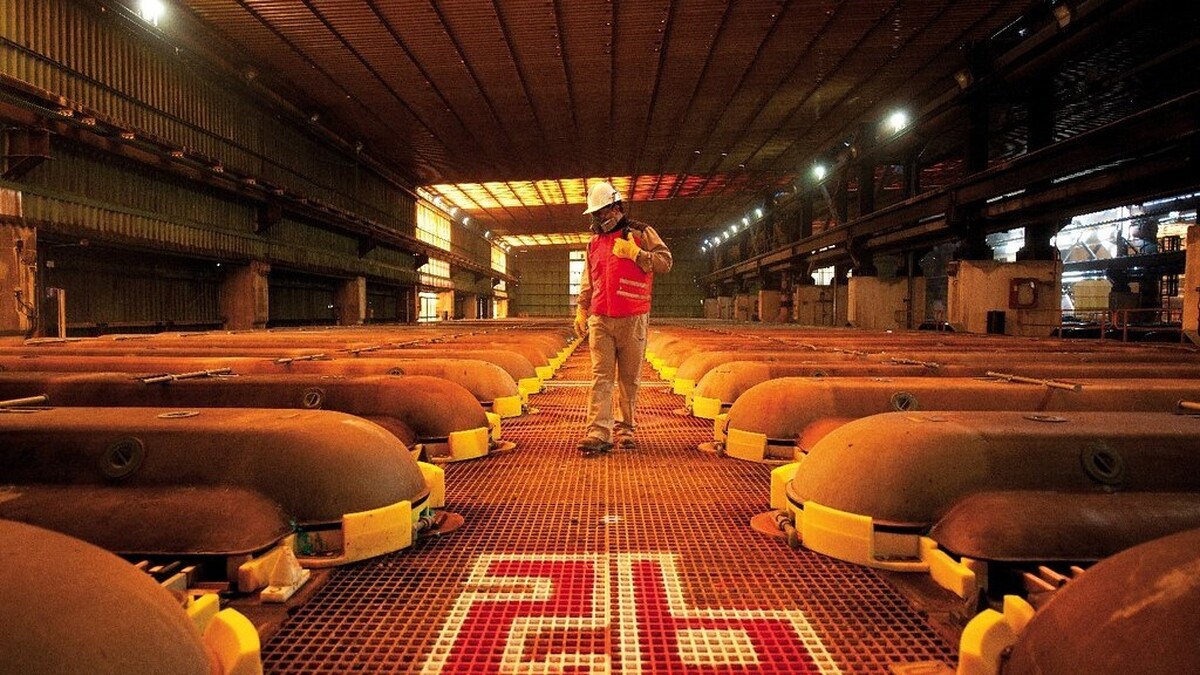

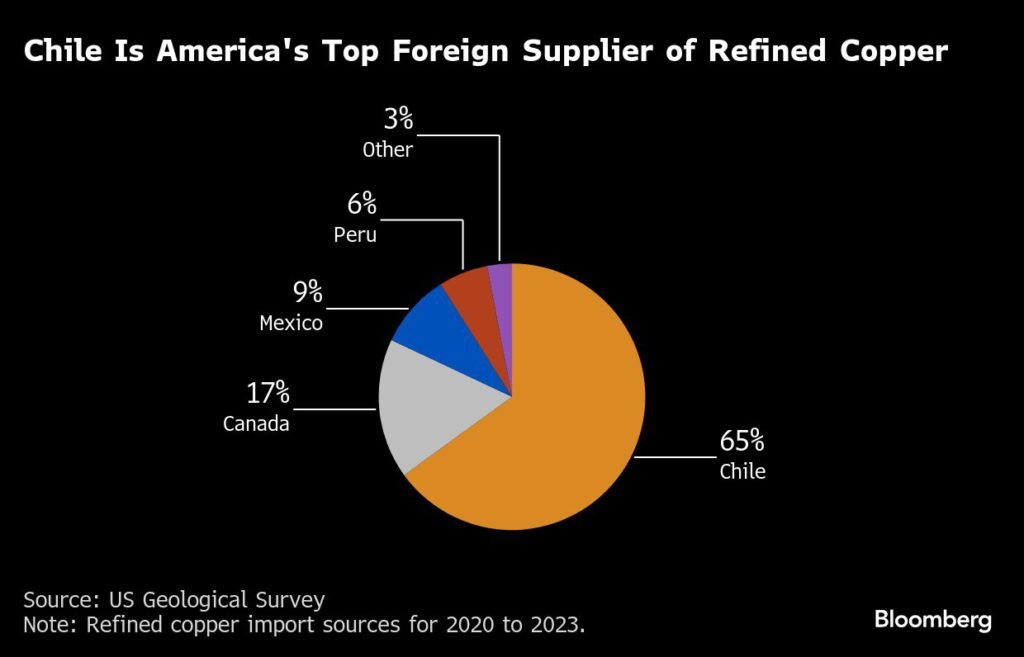

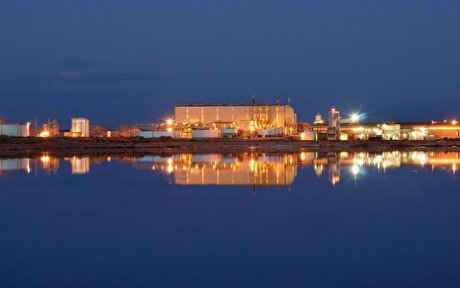

The US consumed 1.6 million metric tons of refined copper last year, with about half coming from abroad, according to US Geological Survey estimates. Chile, Canada and Mexico are the biggest foreign suppliers. Major metals producers including Freeport-McMoRan Inc. and Rio Tinto Group also fill US demand through mines in southwestern states including Arizona and Utah.

US copper prices already reflect the threat of tariffs — they started surging after Trump first floated the idea, with the price on New York’s Comex reaching an all-time high in late March.

Prices have since retreated amid a broad selloff across markets as Trump’s tariffs stoke concern that a recession is coming. Still, Comex copper is about 14% higher this year and carries more than a $700-a-ton premium to contracts on the London Metal Exchange.

RM-Metals, a distributor based in South Plainfield, New Jersey, has seen sales slow over the past two months with customers reluctant to pay higher costs, according to Vice President Sam Desai. The company imports copper wire, rod and strips from Asia and sells to US buyers such as appliance makers.

“For the short term, prices go up — that means everybody has to pay extra,” Desai said.

A 25% copper import tariff would add $68 to $275 in incremental raw material costs to the price of a car sold in the US, with electric vehicles particularly affected because they have about four times as much of the metal, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Data centers that help fill rising demand for artificial intelligence computing are also reacting to the tariff threat. DataBank, a data-center developer, is locking in contracts for copper cable, wiring, pipes and fittings earlier than it planned for projects that are still on the drawing board, and favoring local sources over foreign suppliers.

“This is definitely a high focus point,” said Tony Qorri, who’s vice president of construction at the firm. “Any trade uncertainty will inevitably cloud the outlook of AI development in the US.”

Since copper is a key input for so many products, adding import tariffs is bound to make things more expensive, according to Bart Melek, global head of commodity strategy at TD Securities.

“It ultimately means consumers consume less stuff with copper in it,” Melek said in an interview. “This whole tariff business is reducing consumer confidence broadly.”

source: mining.com

Gold price eases after Trump downplays clash with Fed chair Powell

Copper price hits new record as tariff deadline looms

Brazil producers look to halt pig iron output as US tariff threat crimps demand

Three workers rescued after 60 hours trapped in Canada mine

US targets mine waste to boost local critical minerals supply

Titan Mining targets Q4 2025 to become only integrated US graphite producer

Energy Fuels surges to 3-year high as it begins heavy rare earth production

Glencore workers brace for layoffs on looming Mount Isa shutdown

Resolute publishes initial resource for satellite deposit near Senegal mine

Gold price could hit $4,000 by year-end, says Fidelity

Southern Copper expects turmoil from US-China trade war to hit copper

Ramaco Resources secures five year permit for Brook rare earth mine in Wyoming

Column: EU’s pledge for $250 billion of US energy imports is delusional

Finland reclaims mining crown as Canada loses ground

Gold price down 1% on strong US economic data

Trump’s deep-sea mining push defies treaties, stirs alarm

Chile’s 2025 vote puts mining sector’s future on the line

Gold price retreats to near 3-week low on US-EU trade deal

China’s lithium markets gripped by possible supply disruptions

Gold price could hit $4,000 by year-end, says Fidelity

Southern Copper expects turmoil from US-China trade war to hit copper

Ramaco Resources secures five year permit for Brook rare earth mine in Wyoming

Column: EU’s pledge for $250 billion of US energy imports is delusional

Gold price down 1% on strong US economic data

Trump’s deep-sea mining push defies treaties, stirs alarm

Chile’s 2025 vote puts mining sector’s future on the line

Gold price retreats to near 3-week low on US-EU trade deal

China’s lithium markets gripped by possible supply disruptions