Indonesian nickel ore export ban – implications for nickel supply

Secondly, it is understood that the government wishes to take steps to preserve its nickel resource base to ensure longevity for the existing and future domestic smelter developments. (For reference, the last nickel reserve and resource data provided by the ESDM was in 2014. Total nickel metal resources at that time were stated as 54.54 Mt in 3711.6 Mt of ore. The statement from the ESDM on 2 September suggests current known resources to be 2800 Mt – which pro-rates to 41.1Mt of nickel contained).

Current ore export status

Indonesian ore exports to June total 12.349 Mwmt. Assuming this material to be all grading 1.7% Ni, this equates to around 140 kt Ni. The bulk of this material has been exported to China, with smaller quantities going to Ukraine and Japan. We are aware of there being 36.7 Mwmt of export permits currently in place (although some reports suggest 38 Mwmt). Of these, 8.55 Mwmt expire at the end of September, and a total of 18 Mwmt expire by the end of 2019.

To date, monthly Chinese imports of ore from Indonesia has averaged around 23 kt Ni in ore, equivalent to 280 ktpa nickel. If all the available permitted quotas were used in 2019, then, in theory, Chinese imports could be closer to 400 kt Ni contained.

Given the ban on ore exports now being imposed by year end, it is highly likely that export tonnages will rise significantly between now and December. If arrivals follow a similar pattern to that shown in 2014 and the prior ban, then significant tonnages would continue to arrive in January and February of 2020.

Can the loss be made up from elsewhere?

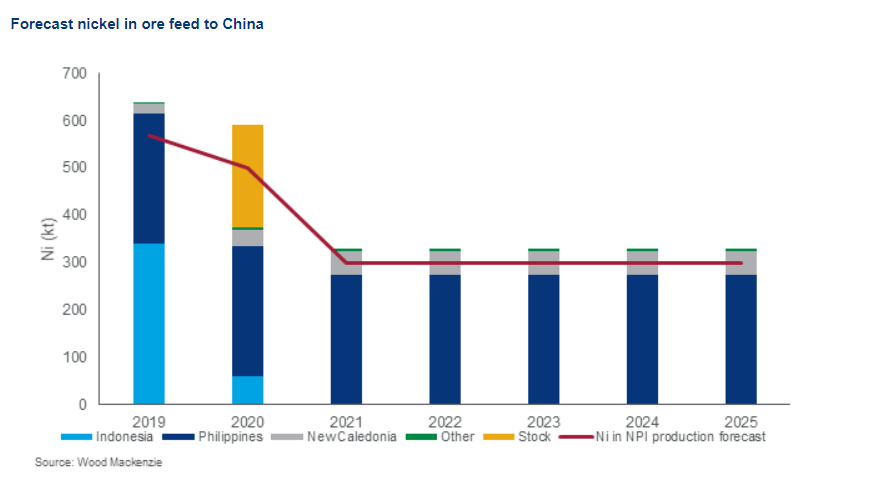

New Caledonia is ramping up its exports to 4 Mwt from 1.57 Mwt in 2018. Guatemala is facing potential cut backs should Solway’s Fenix operations have to close due to local environmental and political issues – although Chinese imports from Guatemala were only around 300 kwmt in 2018. However, these are small suppliers compared with the Philippines, which is viewed as the main potential source of additional ore to offset any loss of Indonesian material.

In 2014, when the initial ore export ban was put in place, the Philippines raised ore exports to China from 29.6 Mt (dry basis) in 2013 to 36.4 Mt in 2014 and 34.3 Mt in 2015. Since that time imports into China have averaged around 30 Mt and look likely to be around the same level for 2019. The increase in production was predominantly achieved by increased production from mines in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), in particular from Tawi Tawi.

However, some mines in the Tawi Tawi region are apparently nearing exhaustion. For example, SR Languyan, one of the largest mines in the Philippines, exporting around 800 ktpa (wet) of high grade ore, is expected to cease production by the end of the year.

It is also reported that the Philippines Minister of Resources will issue a decree to suspend all mining activities in the ARMM, as the local government needs to impose profit sharing agreements and review tax and environmental compliance.

In addition, there is another round of country-wide environmental inspections underway and there are restrictions on the area of a mine site that can be operational at any one time. These all signal that the average 30 Mtpa that the Philippines has exported to China in the past three years is unlikely to increase; indeed, it is more likely to decline.

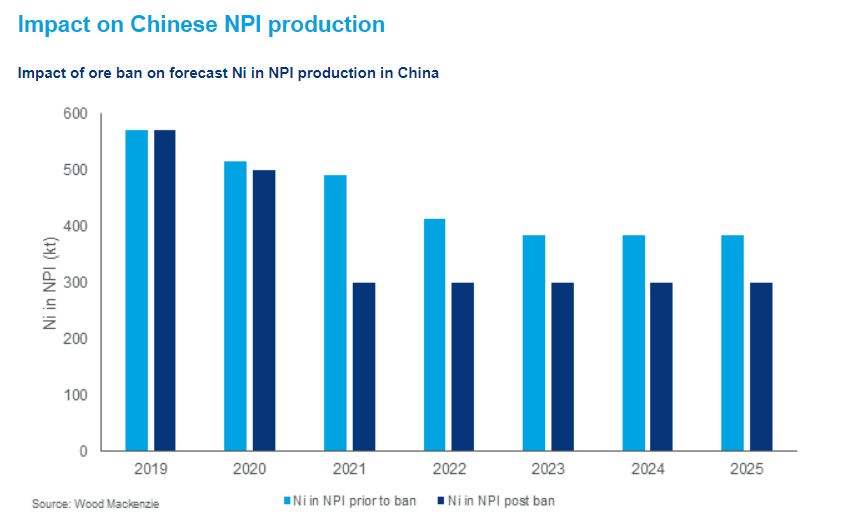

For 2019 there will be no impact on Chinese NPI production and we continue to forecast 570 kt Ni in NPI.

Looking ahead, if we assume imports from the Philippines continue at around 30 Mt, equivalent to ca. 275 kt Ni, and New Caledonia reaches its 4 Mwmt annualised rate from the H2 2020, equivalent to ca. 50 kt Ni, and we assume a further 5 kt of nickel from other ore sources (Guatemala, Turkey, Albania), then the total “secure” long-term feed is sufficient for around 300kt Ni in Chinese NPI, after taking account of recovery losses in processing. Therefore, from 2021 Chinese Ni in NPI production will decline from our current forecast of 490 kt to 300 kt and remain at this level going forward as a maximum. As noted, it is our view that Filipino ore export volumes will decline in 2020 and beyond and, therefore, are unlikely to provide the 275 ktpa indicated above.

For 2020 the impact on our view will probably be less significant. It is safe to assume that those producers with export licences will endeavour to export as much material as possible before year end. Also, as noted above, following the ban in 2014, a further 10 Mt arrived in China in January and February of 2014 – presumably as a consequence of shipments having left Indonesia prior to the 11 January cut-off date. On this basis, up to a further 260 kt Ni in ore could arrive in China before the ban comes into force.

So assuming the supply of 275 kt from the Philippines, 400 kt from Indonesia and 20 kt from New Caledonia, plus a further 5 kt from other sources, total nickel-in-ore feed for 2019 could reach 700 kt, equivalent to around 630 kt Ni in NPI. Based on our forecast for 570 kt for the year, this would leave enough nickel in ore in 2020 to produce around 60 kt Ni.

Combining with the 300 kt detailed above of ongoing feed would suggest a production rate of 360 kt Ni in 2020. However, we are aware that some NPI plants are holding around 4-6 months of ore stocks. While it is not possible to quantify the absolute stock being held by the smelters, if we take a view that the top five producers at least have four months’ stock, this would sustain output of approximately 110 kt Ni in NPI. In addition, port stocks in China are indicated to contain around 115 kt Ni.

Assuming all this stock is utilised, then the combined potential for Ni in NPI in China for 2020 would be 574 kt. Our current forecast for 2020 stands at 516 kt. Thus, for the present, this level of production would still appear achievable. That said, the estimates above for available feed should be viewed as a maximum. Consequently, we have made a modest downward revision to 500 kt. Further revision will be necessary dependent on the volumes of ore exports Indonesia achieves in the coming months.

Can Indonesian NPI production increases offset the supply lost in China?

We estimate the total loss in nickel production because of the ore export ban at 16 kt in 2020, 190 kt in 2021, 112 kt for 2022 and 85 ktpa from 2023 onwards. However, there are smelter projects planned in Indonesia, as well as latent capacity that was idled due to low nickel prices and high coke prices, that in theory could come back into production.

The total idled capacity stands at around 50 ktpa Ni. We have a further 40 ktpa of nickel production in our probable projects. However, development of these to production status will take at least two years. The most likely source of any near-term production response will be from existing smelters. Capacity additions at Indonesia’s industrial parks can be added very quickly. By example, four new lines were added at the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) and commissioned within 15 months (for a total capacity of ca. 36 kt Ni). Tsingshan will add a further six lines over the course of 2019 and potentially a further two in 2020. While production from these expansions are already accounted for in our supply outlook, Virtue Dragon (Delong) has suggested that its stage 2 expansion in Konawe could add another 35 RKEF lines to the existing 15. Potentially this could add over 250 kt Ni in NPI production in Indonesia.

In theory therefore, Indonesia could easily offset the loss in NPI production in China. In reality, the capacity expansion at Virtue Dragon is likely to be slow (past performance indicates that Virtue Dragon cannot add capacity as quickly as Tsingshan at IMIP). Therefore, offsetting the total production loss estimated for 2021 is unlikely. Beyond 2021, the potential for Indonesian NPI production to compensate for the loss of output in China is much more likely.

Summary

The early implementation of an ore export ban by Indonesia is, in our view, unlikely to impact nickel production in 2019. Likewise, while it is probable that we will need to reduce out Chinese nickel in NPI production from the current forecast of 516 kt, this could still prove conservative depending on how much ore permit holders manage to export over the remainder of 2019 and into early 2020. From 2020, the export ban is expected to result in a loss of 16 kt, 190 kt in 2021, 112 kt in 2022 and 85 ktpa from 2024 onwards.

We do not believe that the total forecast loss in production in 2021 can be offset by a production increase in Indonesia. For 2020, should the nickel prices remain at current levels, it will be sufficient to support the reactivation of around 50 kt of idled blast furnace capacity, offsetting the modest production loss forecast.

For 2021 we do not believe that the loss of 190 kt of production can be offset by increases in output elsewhere. From 2022 onwards, our view is that the bulk of the lost output could be offset by increased output in Indonesia assuming funds can be secured for the planned expansions.

Gold price eases after Trump downplays clash with Fed chair Powell

Copper price hits new record as tariff deadline looms

Brazil producers look to halt pig iron output as US tariff threat crimps demand

Three workers rescued after 60 hours trapped in Canada mine

Gold price could hit $4,000 by year-end, says Fidelity

Chile’s 2025 vote puts mining sector’s future on the line

US targets mine waste to boost local critical minerals supply

Energy Fuels surges to 3-year high as it begins heavy rare earth production

Glencore workers brace for layoffs on looming Mount Isa shutdown

Trump tariff surprise triggers implosion of massive copper trade

Maxus expands land holdings at Quarry antimony project in British Columbia

BHP, Vale accused of ‘cheating’ UK law firm out of $1.7 billion in fees

Southern Copper eyes $10.2B Mexico investment pending talks

American Tungsten gets site remediation plan approved for Ima mine in Idaho

Kinross divests entire 12% stake in Yukon-focused White Gold

Gold price could hit $4,000 by year-end, says Fidelity

Southern Copper expects turmoil from US-China trade war to hit copper

Ramaco Resources secures five year permit for Brook rare earth mine in Wyoming

Column: EU’s pledge for $250 billion of US energy imports is delusional

Trump tariff surprise triggers implosion of massive copper trade

Maxus expands land holdings at Quarry antimony project in British Columbia

BHP, Vale accused of ‘cheating’ UK law firm out of $1.7 billion in fees

Southern Copper eyes $10.2B Mexico investment pending talks

American Tungsten gets site remediation plan approved for Ima mine in Idaho

Kinross divests entire 12% stake in Yukon-focused White Gold

Gold price could hit $4,000 by year-end, says Fidelity

Southern Copper expects turmoil from US-China trade war to hit copper

Ramaco Resources secures five year permit for Brook rare earth mine in Wyoming